Thought Field Therapy – The missing link to effective trauma-informed care and practice

By Christopher Semmens Clinical Psychologist Perth, Western Australia

All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident. Arthur Schopenhauer

There is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous to conduct, or more uncertain in its success, than to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things. Niccolo Machiavlli

Trauma- informed care and practice is a framework for the provision of services for mental health clients that originated in the early 1990s and has especially been put forth as a sensible service model since Harris and Fallot’s 2001 publication Using trauma theory to design service systems. Trauma-informed care can be seen to be characterised by three main considerations in regard to the provision of treatment services:

- That they incorporate a recognition of the reality that there is a high incidence of traumatic stress in those presenting for mental health care services.

- That a comprehensive understanding of the significant psychological, neurological, biological and social manifestation of traumatic and violent experiences can have on a person.

- That the care provided to these clients in recognising these effects is collaborative, skill-based and supportive.

In Australia these ideas were the focus of a consciousness raising conference: Trauma-Informed Care and Practice: Meeting the Challenge conducted by the Mental Health Coordinating Council in Sydney in June 2011. The conference was part of an initiative towards a national agenda to promote the philosophy of trauma-informed care to be integrated into practice across service systems throughout Australia.

It has only really been since studies such as the National Comorbidity Study (Kessler et al., 1995); the Adverse Childhood Experiences study (Felitti et al., 1998); and the longitudinal prospective follow up study, the Child Development Project (e.g., Egeland, 2009) has the mythical expectation that exposure to traumatic stress was a relatively rare event has been exploded. We are now operating from a much more realistically informed basis in regard to the quite common incidence of traumatic stress in the general population. Unfortunate figures such as that between 25 and 30% of women have been sexually abused in some way before the age of 18 are now not a surprise to informed health services practitioners. Also there are reliable estimates that as many as 90% of public mental health clients have been exposed to traumatic stress and most have had multiple experiences of trauma.

It was mainly due to the dual political mobilisations of the Vietnam war veterans and the women’s liberation movement of the 1970s that eventuated in the DSM – III of 1980 featuring for the first time the diagnostic category of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Herman, 1992). The advent of the PTSD diagnosis relieved the burden of non-recognition that traumatised combat veterans who went before had to bear where their condition was viewed as a non-compensable manifestation of a characterological weakness.

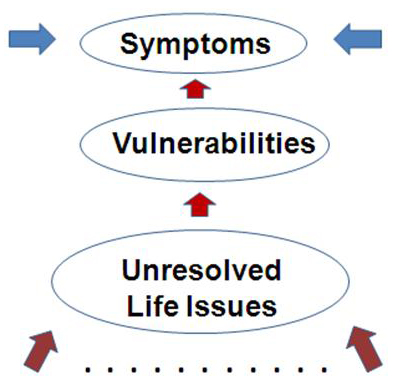

This, of course, was a significant advance. But nonetheless there remain significant limitations to the clinical practicalities related to this advance that are essentially embodied in the medical model mindset within which this PTSD diagnosis is applied. To my mind PTSD has better utility as a legal term rather than as a clinical entity. The requisite number of ticks applied to the 17 symptoms in the right clusters is not going to make much difference to the way that I approach the treatment of a client. The PTSD diagnosis fits with the medical model question: “What is wrong with you?” (See Figure 1).

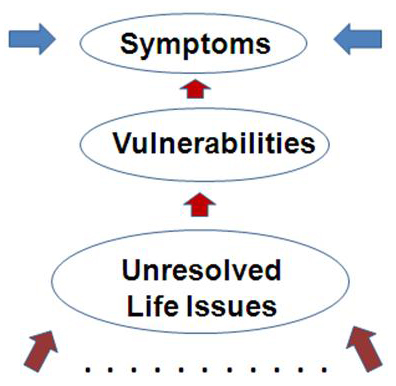

The trauma-informed movement, on the other hand, points to an orientation towards a client where the question is: “What has happened to you?” Symptoms are here seen as manifestations of (or, as some have persuasively put, attempted solutions to) the unresolved life issues that, one way or another, to a greater or lesser degree, most of us carry (see Figure 2).

While this model of service delivery is enlightened by a focused awareness of the stark realities of the circumstances of the people who find their way into our care, rather than essentially a pigeon-holing or labeling exercise that the process of diagnosis can cynically be viewed as, conventional approaches to actually resolving the distress-laden life issues and the instances of traumatic stress that may be revealed through this lens remain cumbersome and in the main lack user-friendliness. Currently what is regarded as the “gold standard” approach to traumatic stress is a prolonged exposure protocol that does not readily lend itself to dealing with multiple unresolved life issues and instances of traumatic stress.

The remarkable discoveries forged by Dr Roger Callahan (1995) under the banner of thought field therapy (TFT) since 1979 would seem to be perfectly suited to be applied within the trauma-informed model. I have been operating from essentially a trauma-informed approach from early on in my utilization of TFT approaches in my clinical psychology practice which has been since 1997. I have done this without actually being aware of, until fairly recently, the formal trauma-informed movement.

I spell out to clients my framework (Figure 2) and sensitively ask them what I call the “four questions plus one”.

These are:

“Tell me about your life – has there been any trauma, disruption or loss in your life?

How was the parenting that you got from your parents?

Is there anything else that you think I ought to know?”

These questions can be asked with great confidence of being able to, in most cases though not all, quite quickly resolve any distress or disturbance that might thus be revealed as being associated with these issues. Utilising such a trauma-informed approach has facilitated the often rapid and remarkable success in the treatment of all sorts of presenting problems.

Particularly illustrative of this approach in action – a trauma-informed attitude to the presenting problem together with the utilization of TFT in the resolution of the revealed life traumas and issues – have been a number of stunning successes in areas where there have been years and years of the very best of what medical model providers have offered without success. I have had repeated successes in two particular areas along these lines – non-specific infertility and migraine headaches.

In cases that include: 4 years of unsuccessful IVF; 6 years of unsuccessful IVF; referral from an IVF clinic, at client’s request, just prior to instituting IVF procedures; 15 years of medical model migraine treatments; and 10 years of conventional migraine treatments – the questions that I asked in the first session (the 4 questions plus one) had not been raised in any of these conventional medical model approaches over all of those years.

In all of these examples there were significant unresolved life issues, with elevated levels of emotional distress and pain associated with them, that were revealed with those questions and which were quite quickly (within a few to several sessions) resolved through the application of TFT techniques with resultant pregnancies (in the first two cases within a week of termination of our therapy) and alleviation of migrainous interference to the lives of the migraine sufferers.

It is curious that despite such stunning successes, repeated around the world every day, together with the recent publication of David Feinstein’s current review of the evidence for the effectiveness of TFT approaches in an American Psychology Association (APA) journal (Feinstein, 2012), guardedness, suspicion and resistance continue to abound–perhaps something to do with the practical reality and applicability of the wise words beneath the title above.

excerpted from Tapping for Humanity, Fall 2012